Lygia Pape with “Amazonino”, 1990

Exhibition at Galeria Thomas Cohn, São Paulo, Brazil

Between the eye and the spirit

Fernando Cocchiarale, 2004

Lygia Pape and the renewal of Brazilian art

Lygia Pape is of the same artistic generation and aesthetic affiliation as Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, and like them, she was a member of the Grupo Frente (1953), the core of the Concretist movement in Rio de Janeiro. Throughout the 1950s, along with the other artists of this group, she developed poetic differences with the São Paulo concretists, until they split into a dissident Neoconcrete faction, which in 1959 became formalized in a manifesto and an exhibition. Pape is accordingly one of the most important artists in Brazilian history. Along with Clark and Oiticica, she was in the forefront of the most creative avant-garde that Brazil has ever seen. The resonance of her work cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the contribution of her experimental disquiet to that founding moment of Brazilian contemporary art.

In a recently published text about the work of Pape, A Lógica da Teia (The Logic of the Cobweb), English critic Guy Brett notes that “It was this rebellious spirit in the Brazilian avant-garde of the fifties and sixties that enabled it to penetrate the ideas of European abstraction deeply without any over-respectful solemnity or feeling of inferiority. These artists could therefore aim at the universal, even the cosmic, while immersed in the local and particular. They were able to escape the typical fate of ‘third world’ artists of providing the metropolis with images of exotic escape. Instead they drew on Brazilian reality to tackle some of the deepest contemporary dilemmas.(…) These artists’ work cannot be fitted into the schema of postwar art history as a local variation of movements centered in Europe or North America. The particular fusion they made must, as it becomes better known, change some of that history’s basic tenets of interpretation. In the process the link between Brazilian artists and certain artists in the west – especially with respect to innovations in ‘the participation of the spectator’– will also become clear.” 2

The first exposure that Guy Brett had to contemporary Brazilian production took place in the 1960s. He realized that some of the artists of the Brazilian avant-garde were expressing in an explicit and unprecedented way the overcoming of a constitutive standstill in western culture: the duality between body and mind, between the sensory and the intellectual, between the eye and the spirit.

Lygia Pape and Guy Brett mounting “Book of Architecture”, 2001

Exhibition “Forma Brazil”, Americas Society, New York, USA

Coming from a British critic, whose interest in Brazilian art was supposedly motivated by his interest in a series of intellectual/artistic questions rather than any facile nationalism, as could be argued had it come from Brazilian critics, Guy Brett’s evaluation is not only unparochial, but also flattering and revealing. It draws our attention to an exceptional phenomenon: that artistic production from South America, Brazil and principally from Rio de Janeiro managed, against the odds, to overcome a cultural equation that still holds sway in Latin America: the valorization of national and popular themes as a factor in local resistance to a European colonizing universalism. In this way, fifty years ago, it managed to lay the foundations for an art that is simultaneously unique and universal.

Because it is responsible for the valorization of its thematics as opposed to formal interests, an equation that privileges the local in such a manner places modern artistic production from the so-called third world on an different footing to that of the classically European vanguards. By moving away from the specialized domain of form and languages toward themes of extra-artistic content (whether social, mythical, regional or national) our artistic production has typically destroyed any possibility of alternative contraposition or dialogue with international art. The supposed defense of our own values, rather than making stand out from the European and American avant-gardes, differentiating us, had as a concrete result the self-exclusion on the part of Brazilian art from international debate and research into new artistic languages for three decades. We were only able to get beyond that impasse in post-war Brazil when abstractionism and constructivism managed to penetrate the country. Rejecting thematicization, abstract art forced us to enlist in the ranks of formalism, condition which was indispensable to the consolidation of Brazilian modernism and its subsequent development in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

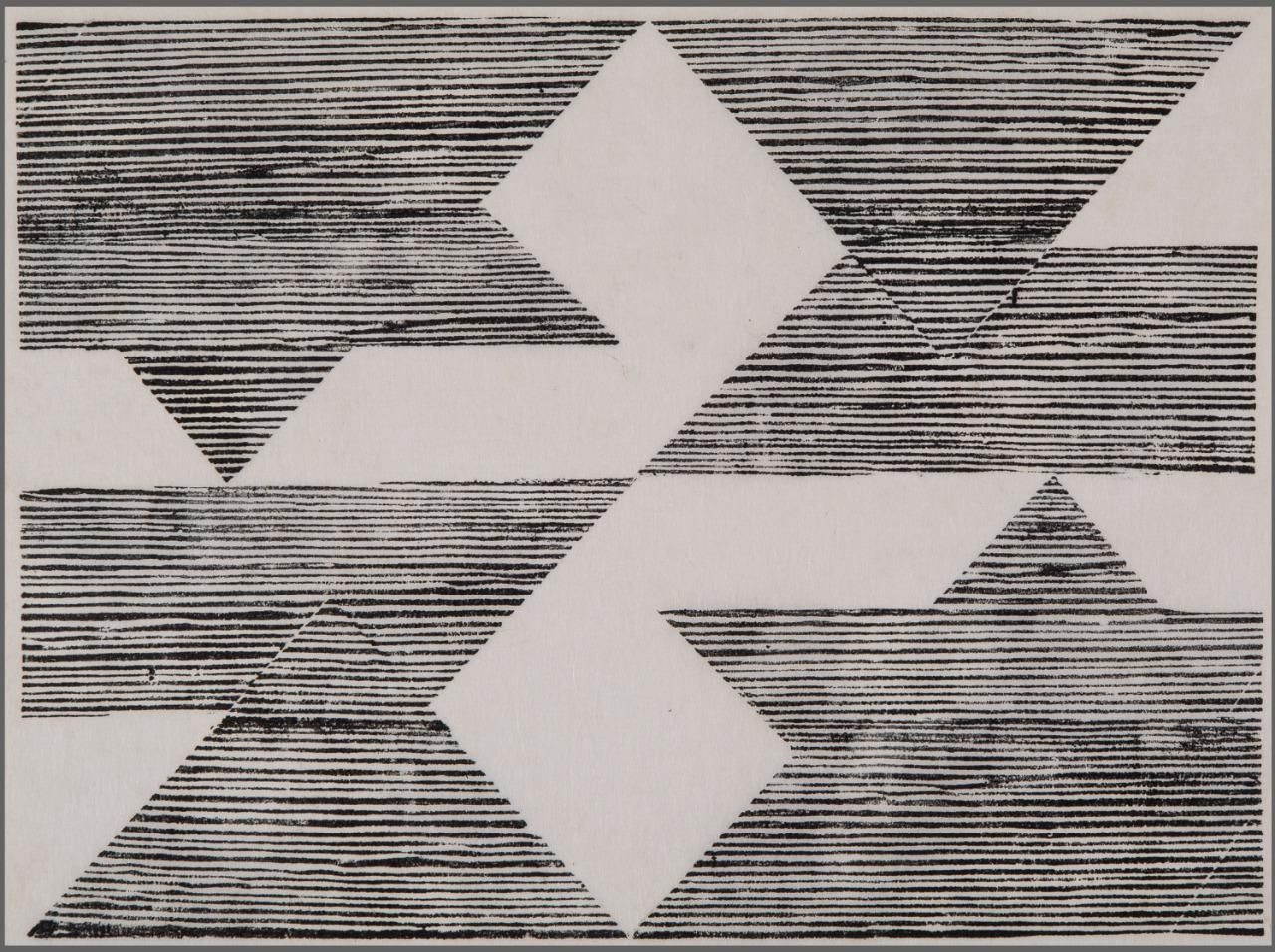

“Tecelar”, 1957

However, the renovating wave that swept the art of the country was not homogeneous, given that the plurality of the Brazilian cultural environment (although still considered to possess a somewhat narrow focus when compared the abstract and constructivist tendencies that were developing at the time) encouraged debate rather than any uniformization of ideas and projects. From a background shaped by differing proposals for modernization, the most radical of them, and the only tendency that completely corresponded to the rebellious spirit mentioned by Guy Brett and which produced solid proposals for dealing with the resolution of the body/mind dichotomy was that of the Neoconcreta (1959). For a whole decade, some of its members, such as Lygia Pape, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica experimented with the consolidation of the peculiar Brazilian modernist experience, as well as attempting to go beyond it, means of proposals that were in tune with an emerging contemporaneity.

A bit of history

Between 1947 and 1951, the circuit of Brazilian art went through radical transformations: in this short period of time leading cultural institutions were created, such as the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (1947), the modern art museums of São Paulo (1948) and Rio de Janeiro (1948), and finally the São Paulo Biennial (1951).

Behind those actions there was a new phenomenon. All these institutions were a result of projects that were conceived and carried out as a result of private initiatives. For the first time in the cultural history of Brazil, the dominant classes were accepting their cultural responsibility, traditionally delegated to the state. This exceptional behavior on the part of the Brazilian elites (exceptional because afterwards the situation returned to what it was before) may be explained by the enthusiasm brought about by the defeat of the Axis powers, in which Brazil participated on the side of the Allies. The triumph of the Allies, and in particular the heightened profile of the part played in this by the United States, influenced us to the extent of determining the definite replacement of European cultural paradigms, particularly the French (which had dominated Brazilian life since the reign of D. Pedro II), by American ones. Like the business community in the United States, Brazilian business people desired, albeit for a brief period, to participate actively in the cultural renewal of the country.

The sudden circulation of works by an international avant-garde in these newly created institutions soon had effects. Our timid modernist production, which up until then had been guided by social realism, saw the emergence of the first groups of young abstract-concrete artists both in Rio de Janeiro and in São Paulo, much to everybody’s disapproval. However, there are other factors which contributed to the transformations that occurred in post-war Brazilian art that must be taken into consideration: the beneficial presence in the country of artists who brought a breath of fresh air, artists such as the Portuguese painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva and Arpad Szènes, who moved to Rio de Janeiro because of the war, and the return of exiles after the end of the Vargas dictatorship (1937-1945) such as the critic Mário Pedrosa. 3

By the end of the 1940s, both in Rio de Janeiro and in São Paulo, the embryos of the concretist groups ‘Frente’ and ‘Ruptura’ were already taking shape, although these groups did not come into full existence until the beginning of the 1950s. Side by side with other artists who entered the informal road of abstraction, these young artists would become the agents of the great transformation that Brazilian artistic production would soon be undertaking.

Although international art hovered around the subjectivity that was inherent to abstract art (American Abstract Expressionism, European Informal Abstraction and, later Tachism), in the case of Brazil (as well as in countries like Argentina and Venezuela), the objectivity of constructive ideas penetrated much more deeply. This preference was certainly determined by the political, social and cultural situation in Brazil at the time.

A period of intense industrialization for the country, the 1950s mobilized important sectors of art and intellectuals around the ongoing transformations, which had as a symbol the construction of the new capital city, Brasília, inaugurated in 1961. Under the sign of change, the artists had no room for doubts. Between the popular traditions cultivated by social realism, which dominated art in the country and kept its followers hostages to the past, and the discipline inherent in constructivism, which allowed its practitioners to project the future, artists increasingly chose the latter, despite the risks that the new always carries.

The concretist groups of São Paulo, ‘Ruptura’, started in 1952 (Lothar Charoux, Hermelindo Fiaminghi, Geraldo de Barros, Judith Lauand, Luiz Sacilotto, Waldemar Cordeiro, etc.) and Rio de Janeiro, ‘Frente’, initiated in 1953 (Amílcar de Castro, Aluísio Carvão, Décio Vieira, Ferreira Gullar, Hélio Oiticica, Ivan Serpa, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Weissmann, etc.) worked from different principles from the start. While the former proposed obedience to the formal, chromatic and spatial principles formulated by Concretism (in 1930 by Theo Van Doesburg, and later, in 1935, by Max Bill), the latter shied away from adherence to such principles, given that they considered the specific and personal character of their experiences to be essential.

If loyalty to the principles of Concrete Art placed the production of the ‘Ruptura’ group within the sphere of reason, the valorisation of experience on the part of the ‘Frente’ group led to its members moving between reason and sensibility without hierarchically privileging one or the other. Such a basic difference has determined a tense and polemical relationship between the two groups, despite their geometrical common denominator.

On the occasion of the 1st (and only) Exhibition of National Concrete Art, in December 1956, in São Paulo and in February 1957 in Rio de Janeiro, the two groups finally had the chance to confront each other and reveal their differences to the audience.

From that moment on, the dissonance between the groups became even more radical, to the extent that, after prolonged debate throughout the media, the ‘Frente’ artists officially broke off their connections to the ‘Ruptura’ group in 1959 and created Neoconcretism.

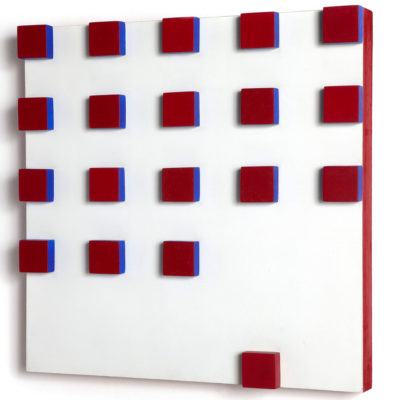

“Relief”, 1954/56

Contrary to what might be expected, the main legacy of Neoconcretism for Brazilian contemporary art has not been formal (construction), but methodological. It consists in the valorization of the experimental (process) above any normative principles that are perceived as having the potential to limit intervention. The originality of the works by Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape, for example, should be credited to this spirit of experimentation, which allowed them to overcome the formal questions of Concretism and later of Neoconcretism, rather than to the strict option in favor of geometry, an option taken by other sectors of the Brazilian vanguard without the same results.

Lygia Pape’s contribution

A common denominator in the poetics of all neoconcrete artists was the search for the effective integration of the space of the work with real space. To achieve this, they shifted the opposition between form and background, once restricted to the internal physical limits of the works, to the integration between work and real space. What they were proposing was a new perception in which the background was not restricted to the objective dimensions of the work’s materiality, for the deliberate suppression of the frame, in bi-dimensional works, and the base in tri-dimensional ones, aimed at the overcoming of the existing dualism between the conventional space of art and real space, the place of art and the world.

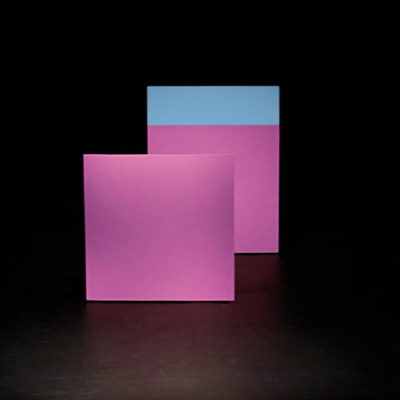

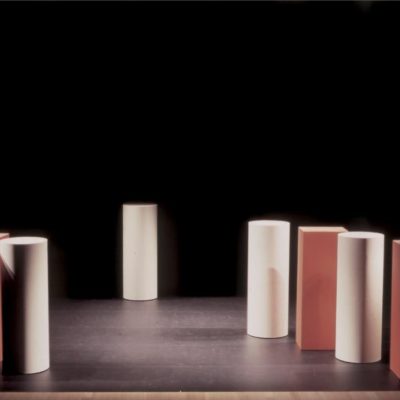

“Neoconcrete Ballet N. 2”, 1959

With respect to this central question in the practice of Neoconcretism, Lygia Pape (referring to her Ballet Neoconcreto nº 2, presented in Rio de Janeiro in 1959) described it thus: “During the presentation a special moment took place, when the pink board started to back towards the infinite black, and suddenly you got the impression that the pink, which was matter, was transforming itself into space, and the black into form. A type of ambivalence that resembles what happened in my print”… 4

The formulation of the question of dualism developed slowly, and in different degrees, in the progression from the ‘Frente’ group to Neoconcretism. In the case of Pape, this process can be observed in her investigation into different surfaces and materialities during this pioneer period.

Her paintings of the ‘Frente’ period, despite not basing themselves on principles of formal sequencing, possess characteristics that are eminently concretist, with a clear distinction between form and background. The dynamic disposition of the formal elements in these works (squares combined with diagonal lines that cross each other, with several angulations with respect to the axis of the paintings) stands in stark contrast to the regularity of her work in relief from the same period.

“Painting”, 1954/56

Her Reliefs do explore sequencing, and yet, however, they integrate it in a set that possesses the solidity of geometrical parquet (squares, rectangles, triangles) and of the square wooden surfaces on which they are glued, in a rhythmic order. Painted in two or three colours, these reliefs are incorporated in the wall (real space) as if they were part of it. Their optical and tactical integration is created through a chromatic artifice: the coloured sides of the art-object contrast with the white on the walls in the same way that the colour on the side of the floorboards stands out from the white on the surface of the works. From these two chromatic breaks between the width and the surface of the wall and the material properties of the work a perceptive feeling of continuity paradoxically arises, which makes the reliefs look like a geometric protuberance on the walls of the exhibition space.

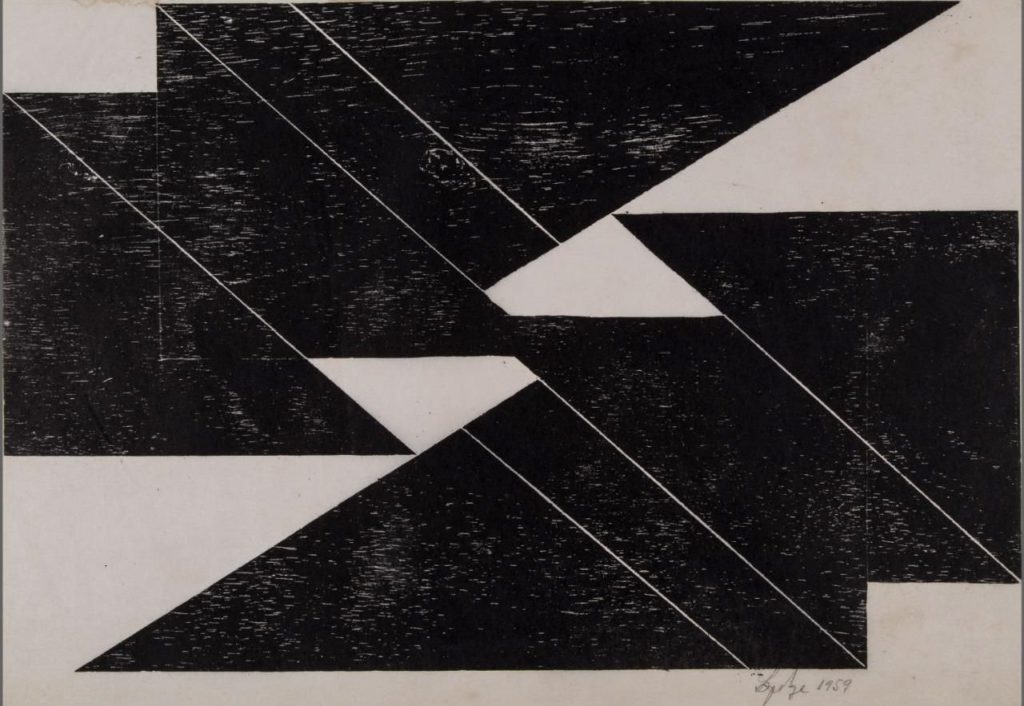

“Tecelar”, 1959

This cycle is completed with the Tecelares (1955/1959), the only examples of neoconcrete xylography, and the Ballets. Around the beginning of the 1960s, Neoconcretism was dissolved, in line with what its manifesto had predicted. 5

While Amílcar de Castro, Franz Weissmann, Aluísio Carvão and Décio Vieira continued to investigate the expressive possibilities of geometric shapes, Pape, Clark and Oiticica’s experiments ended up by expanding the neoconcrete privileging of the insertion of the work into real space. What followed was the challenge of formulating in an experimental and sensitive way the integration of art into life itself.

The Moebius strip 6 is for Lygia Pape a metaphor: “when you have a strip, initially there is always an inside and an outside; but if you twist one of the ends, connect it and run your finger through it, then you don’t have an inside nor an outside anymore. You will have a continuous plane, a concept that goes from an internal space to an external space in a sliding move (…) It introduces the idea of art and life mingling, abolishing or denying the sacralized space of the exhibition room, etc., which moves me a lot.” 7 Whereas Clark’s investigation led her to sensorial interaction, and Oiticica’s encouraged him to search for the painting outside the canvas, leading him towards the spatial and social existence of marginal and marginalised communities; ties; throughout her work Pape has worked on the integration of the aesthetic, ethical and political spheres. That is, she has chosen to act in an ambiguous territory, located somewhere between the collective perception (not only of a historical and cultural content, but also institutional) and the individual perception (both sensorial and cognitive) of Brazilian space and images.

Ballet Neoconcreto Nº 1, 1958

From the xylographs to the neoconcrete Ballets (in which the dancers were reduced to mechanisms, for they only lent the movement of their bodies to the geometric shapes that hid them), presented in Rio de Janeiro in 1958 and 1959; from the Livros da Criação, do Tempo, da Arquitectura [Books of Creation, Time and Architecture] and the Livro da Luz (Book of Light), also called Noite/Dia (Night/Day) conceived between 1959 and 1960 (object-book whose cover-boards are chromatic, formal and spatial diagrams of creation and of our creations, of the passing of time and the historicity of spaces constructed by human beings), through her experimental films (1966-66) and her participative experiments (O Ovo [The Egg] and Divisor [Divisor], for example, presented for the first time in the gardens of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, in 1968), a progressive proximity to life has introduced, in Pape’s work, temporality (flow) and ‘Brazility’ (narrative).

Time, however, is not simply a representation here. It is mostly a real flow: the flow of parts that unfold in time (Livro da Criação [Book of Creation], Ballets, for example), the flow of performances (O Ovo [The Egg]) and the flow of the participation of the audience (Roda dos Prazeres [Wheel of Pleasures], Divisor [Divisor]), the flow of Brazilian history and memory, and finally, the flow of Pape’s own experience, which has been marked by the constant transformation of the means and the results of her production.

“Book of Creation” (and Man invented the Wheel), 1959/60

At the end of the 1960s, a period of great political oppression on the part of the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964-1985), her works turned to the critique of the values and discourses of the elites and cultural institutions (A Caixa das Baratas [The Box of Cockroaches], for example, presented a collection of cockroaches arrayed in strict order within an acrylic box).

Lygia Pape was radicalising, by means of non-verbal language, the narrative content that is present, for example in her Livro da Criação (Book of Creation). Amongst all the neoconcrete artists, Pape is surely the one who went deeper in the search for a synthesis of visual language and narrative (commonly associated with verbal discourses).

Both abstractly universal questions (creation, time, space) and those which, although manifested everywhere and in every period of time, are here filtered through the Brazilian experience (violence, sexuality, politics), to themes that are specific to our history (Indians, or the Amazon forest, among others) are translated by visual means. Narrative underlies the process; it takes roots in the verbal economy of the titles of the works and in certain chromatic, iconic and indicative references which are part of the works.

In that respect, Pape’s work takes up Oswald de Andrade’s Anthropophagi, which was presented in São Paulo, in 1928 (Anthropophagous Manifesto). On the question of her relationship with Brazil, Pape said: “There is the question of anthropophagi, the devouring of the culture of the other. I have already made several Tupinambá Quilts. One is a big red cloud over the city, which is only in the book, for it is virtually impossible to make. Because when I cross the Guanabara Bay, I construct a film, I imagine whales, dolphins, the Indians, I dream away, I visit my past, history superimposes itself.” 8

“Tupinambá Mantle ”, 1996/99

The anthropophagous model associated the specific sense of Brazilian cultural production with the cannibalistic rituals of various indigenous peoples. As in these rituals, we would devour the cultural influences that arrived from abroad, digesting them according to patterns that have been ‘Brazilianised’ by previous anthropophagic experiences. This proposal was in tune with experimentalism, at least as far as the valorisation of the process is concerned. 9

The anthropophagous model associated the specific sense of Brazilian cultural production with the cannibalistic rituals of various indigenous peoples. As in these rituals, we would devour the cultural influences that arrived from abroad, digesting them according to patterns that have been ‘Brazilianised’ by previous anthropophagic experiences. This proposal was in tune with experimentalism, at least as far as the valorisation of the process is concerned. 9

Of all of Pape’s works, the most emblematic ones, those that best synthesize her artistic process, are probably As Ttéias, the first of which was conceived in 1979. However, it was not until the 1990s that new versions were produced. As Ttéias are installations constructed by the geometric disposition of golden threads in space. Not only do they outline volumes, but they also draw lines that are nearly invisible.

The Ttéias produce a strong impact by the discrete subtleness of their striking disposition and in terms of the ways in which they reflect light in varying fashion according to the spectator’s position. They outline a spatial diagram very similar to that observable in Tecelares. The wood grain of the matrix, the diagonal disposition of the graphics, the empty spaces and the filled spaces that penetrate each other, everything in the earlier xylographs can be related to As Ttéias, as if both types of work marked the limits of a long trajectory. The silent dazzlingness of these installations can be analogously compared to the lightness and the weight of certain Cathedrals. Lygia Pape died in Rio de Janeiro in May 2004.

“Ttéia 1,C”, 2002

Notes

1 The title takes its inspiration from a text by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose thought served as a theoretical basis for the Neoconcretism’s overcoming of the dualistic concepts of classical art (shape and background, mimetic space and real space, reason and sensibility, project and experimentation, etc).

2 Guy Brett: A Lógica da Téia in Gávea de Tocaia / Lygia Pape, São Paulo, Cosac & Naify Edições, 2000

3 Mário Pedrosa (1900-1981) was one of the greatest critics of Brazilian art, along with possessing a fundamental role in the defense and consolidation of constructivism in Brazil. His work “Da NaturezaAfetiva da Forma da Obra de Arte” (“On the Affective Nature of Form in The Work of Art”) (1949) is a pioneering study in the application of Gestalt theory to the interpretation of art.

4 Denise Mattar: 4 Denise Mattar: Lygia Pape, (p. 67), Perfis do Rio Collection, Relume Dumará / Prefeitura, Rio de Janeiro, 2003.

5 “The participants in this 1 st Neoconcrete Exhibition are not a group. They are not connected by dogmatic principles. The evident affinity between their investigations in various fields has brought them together and linked them here. Their approach however binds them first and foremost to their own experience, and they will be linked together only for the duration of the profound affinity that has brought about their conjunction here.” (Manifesto Neoconcreto, Jornal do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro 23/03/59)

6 The Moebius strip was also a subject of interest for Lygia Clark, who in Caminhando (Walking) uses that topological model as a starting point.

7 Denise Mattar: Lygia Pape, (p. 79), Perfis do Rio Collection, Relume Dumará / Prefeitura, Rio de Janeiro, 2003.

8 Denise Mattar: Lygia Pape, (p. 89), Perfis do Rio Collection, Relume Dumará / Prefeitura, Rio de Janeiro, 2003.

9 Helio Oiticica and several other artists and intellectuals acknowledged the importance of Anthropophagi in the 1960s.

Bibliography

– Amaral, Aracy. Arte Construtiva no Brasil, Adolpho Leirner Collection. São Paulo, Lloyds Bank, 1999.

– Brito, Ronaldo. Neoconcretismo, Vértice e Ruptura do Projeto Construtivo Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, Funarte / INAP, !985.

– Canongia, Lygia. Abstração Geométrica 1 – Construtivismo e Neoconcretismo – Projeto Arte Brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Funarte / INAP, 1987.

– Cocchiarale, Fernando and Geiger, Anna Bella. Abstracionismo Geométrico e Informal: a Vanguarda Brasileira nos Anos Cinqüenta, Rio de Janeiro, Funarte / INAP, 1987.

– Herkenhoff, Paulo. Lygia Pape – Fragmentos, São Paulo, Galeria Camargo Vilaça, 1995.

– Duarte, Paulo Sérgio. Lygia Pape, Rio de Janeiro, Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, 2002.

– Duarte, Paulo Sérgio. Anos 60 – Transformações da Arte no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, ed. Campos Gerais, 1999.

– Mattar, Denise. Lygia Pape, Rio de Janeiro, Relume Dumará / Prefeitura (Perfis do Rio Collection), 2003.

– Oiticica, Hélio. Aspiro ao grande Labirinto. Rio de janeiro. Editora Rocco, s.d..

– Pape, Lygia, Gávea de Tocaia / Lygia Pape. Introduction by Guy Brett. São Paulo. Cosac & Naify Edições, 2000.

– Pape, Lygia, Lygia Pape. Introduction by Mário Pedrosa. Poems by Luiz Otávio Pimentel. Rio de Janeiro, Funarte / INAP (Arte Brasileira Contemporânea Collection), 1983.

– Pedrosa, Mário. Mundo Homem Arte em Crise, São Paulo, ed. Perspectiva,1972